I started writing this blog in 2020 to share my views on macroeconomics and long-cycle investing. My very first piece was a strong call on gold. At the time, I argued that gold was likely to be one of the best investment opportunities of the coming decade. The framework was admittedly abstract: deeply negative real rates, de-globalization pressures, high debt and low growth as the post-pandemic equilibrium, persistent monetary accommodation, and a rising inflationary undercurrent. History suggested that under such conditions, gold will ultimately enter a super-cycle.

Five years later, gold’s price path has unfolded broadly along that thesis. Looking back, the feeling is less triumph than humility. The original conviction was built on a conceptual framework, not on any concrete forecast of events. While extreme real rate dynamics were part of the story and largely within expectations, the actual path the world took was far more dramatic than anyone could have sketched out. We witnessed a major policy misjudgment by the Fed that allowed inflation to surge to 9.1%. We saw aggressive tightening burst the innovation-era bubble, wiping out fragile startups and triggering a regional banking crisis.

My deepest conviction back then, however, went beyond gold as a short-term hedge or even a medium-term real-rate proxy. At its core, gold is a long-term measure of dollar credibility, the monetary reference point against which the dominant country of a Kondratiev cycle is ultimately judged. I believed that as contradictions accumulated, some form of systemic re-ordering was inevitable. What I could not have imagined was how explicitly that process would reveal itself.

The Russia-Ukraine war in 2022, followed by unprecedented financial sanctions and the freezing of sovereign reserves, delivered a profound shock to the notion of dollar neutrality. That moment marked the opening act of de-dollarization—not as ideology, but as risk management. Central banks stepped in as structural buyers of gold. By 2025, escalating tariff conflicts, violent swings in the Treasury market, and the erosion of Treasuries’ safe-haven status further reinforced a simple conclusion: gold had become the only uncontested refuge, effectively replacing U.S. government bonds in the global safety hierarchy.

Over the past five years, maintaining a meaningful allocation to gold has been both intellectually validating and financially rewarding. And as we stand here today, my bullish view on gold remains firmly intact. In what follows, I want to revisit the logic, updated with lived history, and lay out why the forces driving gold higher continue to build as we look toward 2026.

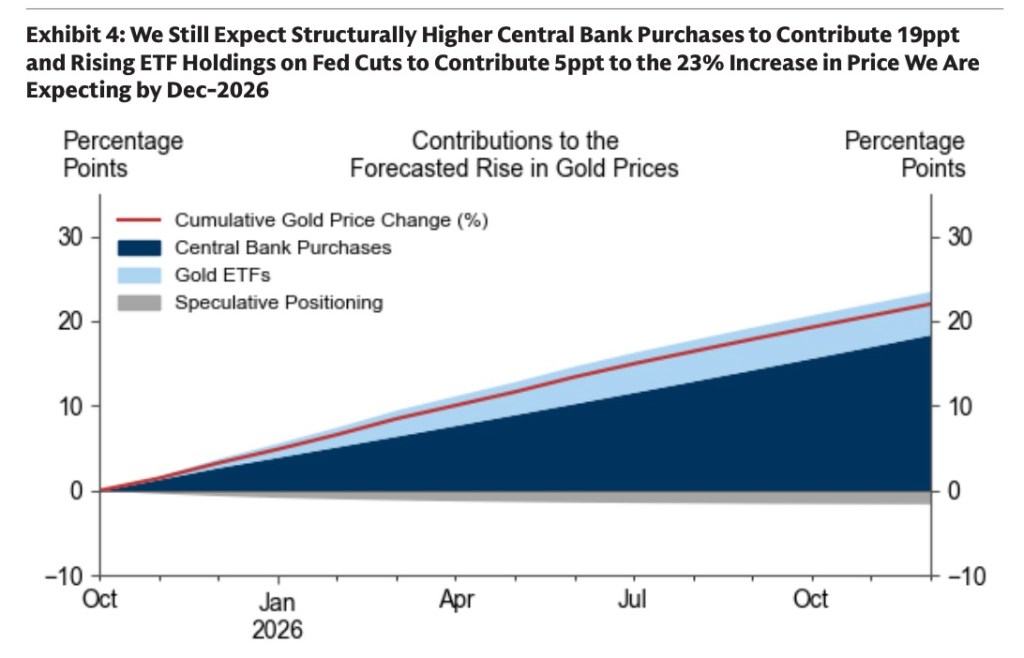

I believe gold is being driven by three distinct forces. The two dominant ones are de-dollarization and safe-haven substitution, while currency debasement, as captured by the real-rate framework, plays a secondary role. In other words, as long as de-dollarization and the repricing of safe assets remain intact, fluctuations in real rates—no matter how dramatic—may create volatility, but are unlikely to alter gold’s long-term upward trajectory.

The first, and by far the most dominant factor, is de-dollarization.

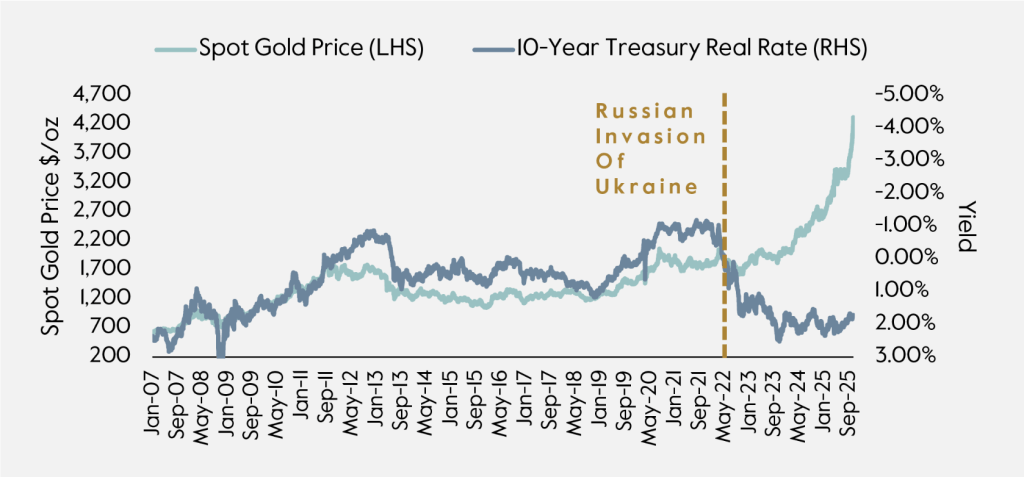

The traditional debasement framework for gold anchored in real rates worked remarkably well before 2022. That relationship, however, began to break down in 2022, when gold sharply disconnected from U.S. real yields under the influence of a new force: de-dollarization.

That year marked a turning point. Western powers froze roughly $300 billion of the Russian central bank’s assets, nearly half of its foreign reserves. While official communication at the time emphasized respect for international law and framed the action as exceptional, very few emerging-market central banks took comfort in those assurances. Instead, many responded by reducing exposure to U.S. Treasuries and reallocating reserves toward gold as a form of self-insurance.

That reaction has since proven prescient. More recently, German Chancellor Merz openly advocated using frozen Russian central bank assets to help finance aid to Ukraine—underscoring that such actions are no longer viewed as unthinkable, but as policy options. History offers a stark warning here. Countries whose central bank assets have been frozen—such as Iran, Venezuela, North Korea, Afghanistan, and Libya—have almost never recovered economically. Iraq remains the lone exception, and only after a complete regime change, with fragility still lingering. In other words, for policymakers, this is a risk that must be avoided at all costs. Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me.

The consequence has been a structural shift in global reserve management. Central banks have simultaneously increased gold holdings while reducing allocations to U.S. Treasuries. In early September this year, when gold reached $3,500 per ounce, it overtook U.S. Treasuries in central bank reserve composition. At today’s price of around $4,500 per ounce, gold accounts for approximately 27% of global central bank reserves, compared with 23% for U.S. Treasuries.

For perspective, in 1970, just before the Nixon Shock ended the gold standard, gold’s share of global reserves stood at roughly 40%. That historical benchmark suggests that, even after the rally we have already seen, the reallocation process may still have meaningful room to run.

What to watch in 2026 are, India has indicated an intention to raise gold’s share of reserves toward 20%, from roughly 16% today. Poland has articulated a target of lifting gold to around 30% of reserves, up from approximately 26%. Turkey continues to view gold as a hedge against persistent currency depreciation and inflation risks. Korea, after more than a decade without increasing gold holdings, has publicly stated that it is considering renewed accumulation. Brazil, where gold still accounts for only about 6% of reserves, has been a notable buyer in recent quarters, highlighting the scope for further diversification.

Second, safe-haven substitution has become a defining feature of this cycle.

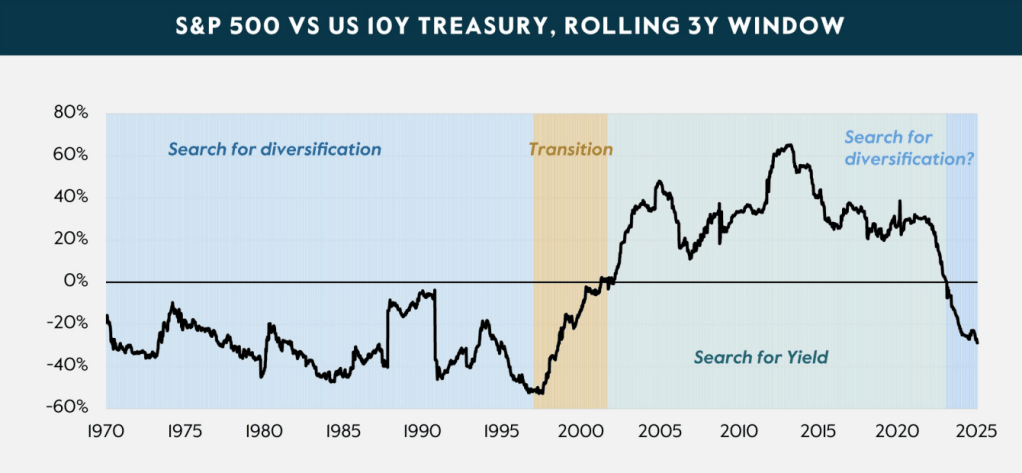

For much of the post-2001 period, asset allocation was shaped by a combination of low interest rates, subdued inflation, excess liquidity, and a persistent global savings glut. These forces compressed risk premia across asset classes and supported stable diversification between bonds and equities. Over the past two years, however, these conditions have steadily eroded—and under the current policy trajectory, they are likely to reverse more forcefully and persistently.

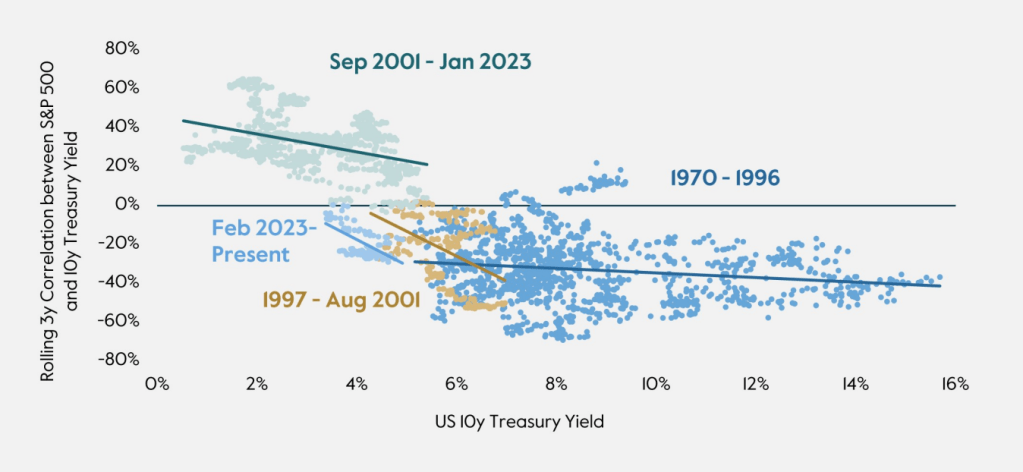

The clearest empirical expression of this shift has been the flip, and subsequent rise, in bond–equity return correlations from structurally negative to decisively positive. In earlier regimes, bonds reliably offset equity drawdowns as negative shocks were translated into easier monetary policy and lower yields. As inflation constraints, fiscal considerations, and supply-side pressures have increasingly limited central banks’ ability to respond symmetrically, that reaction function has weakened. When adverse shocks no longer guarantee falling rates, bonds lose their natural hedging role.

As a result, the traditional 60/40 portfolio is no longer “naturally” diversified. Investors are being forced to look beyond duration for risk mitigation, creating renewed demand for alternative diversifiers—most notably hard commodities, and gold in particular.

That abstraction turned concrete particularly following the April tariff announcements. Rather than triggering the familiar flight into duration, the Treasury market experienced sharp volatility and poor hedging performance. As showed in below, since April, correlations between U.S. Treasury prices and other safe assets, as well as with uncertainty indicators, fell toward zero. This decoupling suggests that Treasuries’ safe-haven properties became more state-contingent, rather than operating as a general absorber of risk. Importantly, this shift appears specific to U.S. assets. Other core bond markets did not exhibit comparable changes. In particular, German Bunds continued to display—and in some cases strengthened—their positive correlation with measures of global risk aversion, underscoring that the episode was not a generalized breakdown of sovereign bond hedging properties.

This results in a vacuum at the top of the safe-haven hierarchy. Capital filled that vacuum decisively. Flows rotated toward gold as a functional hedge. In fact, if we look at a longer period of time in history, safe-haven demand has been allocated across a small set of assets—U.S. Treasuries, the U.S. dollar, and gold, and they substitute for one another at different point in time. At various points in history, the U.S. dollar, U.S. Treasuries, and gold have each occupied the top position in the safety hierarchy. Crucially, substitution tends to occur when one asset enters a visible, long-duration decline—whether through inflation, fiscal erosion, policy constraints, or credibility loss.

Gold’s re-emergence fits squarely within that pattern. Unlike Treasuries, it does not rely on policy easing, fiscal capacity, or foreign confidence of the U.S. to perform its role. As bonds increasingly reflect growth, inflation, and supply risks rather than offset them, gold has been repriced as the residual safe haven—the asset investors turn to when conditional hedges cease to be dependable.

Thirdly, currency debasement, as captured by the real-rate framework, continues to play a persistent but secondary role.

Over long horizons, gold has exhibited a robust inverse relationship with real interest rates, reflecting its function as a non-yielding asset whose opportunity cost is determined by inflation-adjusted returns on cash and sovereign debt. Periods of declining or deeply negative real rates have historically coincided with rising gold prices, as monetary accommodation and inflationary pressures erode the real purchasing power of fiat currencies.

Currency debasement does not require CPI-style inflation. What matters is the erosion of real purchasing power embedded in the risk-free rate. Prior to the GFC, falling real rates were typically associated with physical inflation. Post-GFC, debasement increasingly manifested within the financial system itself—through rising equity and bond prices—rather than through broad-based consumer inflation. From the perspective of real rates, the transmission channel differed, but the implication for gold was the same.

What I would particularly emphasize is the risk of over-relying on the real-rate framework and treating central bank policy as the sole market driver. While real rates remain an important explanatory variable, the current gold market is increasingly shaped by who the marginal buyers and sellers are, and by the nature of their demand.

On the demand side, today’s dominant buyers are central banks as I mentioned in the first part. This includes oil-exporting countries recycling surplus revenues, as well as Asian and Middle Eastern central banks actively increasing physical gold holdings. Crucially, much of this demand is for physical delivery. Gold is purchased, transported, and stored domestically, effectively removed from the tradable float. This creates a form of rigid, cost-insensitive demand that steadily tightens available supply.

On the supply and positioning side, the remaining marginal sellers are disproportionately model-driven investors. Many systematic and algorithmic strategies continue to anchor their positioning to the real-rate framework, expressing short exposure on the premise that sustained high policy rates should suppress gold prices. This creates an asymmetry. As rates rise, these strategies expect headwinds for gold; yet higher rates simultaneously exacerbate concerns around the U.S. fiscal sustainability and balance sheet. Under those conditions, gold can behave in a counterintuitive manner—rising alongside higher rates as it is increasingly priced against sovereign risk rather than monetary accommodation.

In economic terms, this dynamic resembles a Giffen-type behavior: higher “costs” in the form of rising interest rates do not reduce demand, but instead reinforce it by intensifying concerns about the underlying asset backing the system. Each price correction driven by model-based selling has tended to encounter inelastic physical demand, while also forcing short-covering as positions move against expectations. The result is a reflexive process in which pullbacks reduce, rather than reset, upside pressure.

Taken together, this shift in market structure helps explain why gold has remained resilient in an environment that traditional models would have deemed unfavorable. Real rates still matter, but they no longer operate in a vacuum. When sovereign demand dominates the bid and physical supply is progressively withdrawn from circulation, price dynamics become less sensitive to cyclical policy variables and more responsive to structural considerations around credibility, reserves, and balance-sheet risk.

Finally, it is worth emphasizing that gold’s price behavior is inherently multi-layered, reflecting the interaction of several distinct trading logics rather than a single dominant factor.

Over the long run, gold is anchored by structural forces—reserve diversification, safe-haven substitution, and currency debasement. Over shorter horizons, however, its price can be influenced by overlapping and sometimes conflicting narratives, each associated with a different investor base and use case.

In recent months, one such layer has become increasingly visible. Beyond its monetary and safe-haven roles, gold remains part of the broader precious metals complex, which has been affected by renewed enthusiasm around industrial demand linked to the AI and electrification cycle. While gold itself is not a core industrial input in the way copper or silver are, it is nevertheless grouped with precious metals that do have more direct exposure to semiconductor manufacturing, advanced electronics, and energy-intensive technologies. As a result, speculative flows driven by the AI theme have, at times, spilled over into gold, amplifying short-term correlations with risk assets.

This dynamic warrants caution. When gold is partially priced through an “industrial metals” or “technology adjacency” lens, its behavior can temporarily resemble that of growth-sensitive assets rather than that of a pure hedge. In such phases, gold’s correlation with AI-related equities or the broader equity market may rise, potentially diluting its effectiveness as a short-term risk offset. This does not negate gold’s long-term role as a store of value or strategic hedge, but it does suggest that its hedging properties are not invariant across time horizons.

From a portfolio perspective, the implication is straightforward. Gold should not be assumed to provide continuous, linear protection against equity volatility, particularly during periods when thematic enthusiasm—such as the current AI cycle—dominates marginal flows. The asset’s true behavior emerges from the interaction of its monetary, financial, and industrial identities, with the balance between them shifting as market narratives evolve. Recognizing this complexity is essential when assessing gold’s role not just over years, but across the shorter cycles that will likely characterize equity markets in the year ahead.